That was then, this is now: Open season on vaccinating pregnant women

04/23/2018 / By News Editors

Instinctively, most of us know that pregnancy is a time when it makes sense to be cautious. After all, as even popular culture attests, “precious cargo” is involved. With medications, focus group research indicates that when the risks of a given medication are unknown, most women are not willing to take the medication during pregnancy.

(Article republished from WorldMercuryProject.org)

To help pregnant women navigate potential risks to themselves and their “cargo,” WebMD furnishes a long checklist of substances known to cause birth defects, including acne drugs, some antidepressants and heavy metals such as lead and organic mercury. However, when it comes to flu shots (some of which contain organic mercury), the website tells women that the vaccines are completely safe any time during pregnancy. The website’s certitude in this regard rests on the assurances of entities like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which has long recommended influenza vaccines for pregnant women. CDC’s rationale is that the vaccines are needed to help pregnant women avoid the “excess” influenza-related deaths that apparently occurred during early-20th-century influenza pandemics.

Published reports point to an increased risk of miscarriages and elevated risks of birth defects and autism in the offspring of mothers who received influenza vaccines during pregnancy—

Changing recommendations

Around 2006, CDC took stock of the persistently low compliance with its influenza recommendations, largely ignored by both doctors and pregnant women, and began more aggressively promoting flu shots for pregnant women. In an update in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC cited as evidence of the vaccines’ safety during pregnancy a grand total of two retrospective epidemiological studies of medical records—one of which was published in 1973.

In 2011, CDC and other medical trade organizations also began recommending that all pregnant women get the Tdap vaccine (tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis), which, among other ingredients, contains neurotoxic aluminum. Tdap coverage in pregnancy increased substantially following this recommendation, particularly in women who also received other vaccines during pregnancy. The FDA’s original approval of the two Tdap brands (Boostrix and Adacel) in the mid-2000s was as a booster for teens and adults, and the product inserts state that Tdap should be given during pregnancy only “when benefit outweighs risk.” At the time of the 2011 recommendation, no prelicensure studies of Tdap safety during pregnancy were available, so most of the (largely unpublished) data used to justify the recommendation came from post-licensure pregnancy pharmacovigilance conducted by vaccine manufacturers. To this day, online information for Boostrix states that “it is not known whether Tdap vaccine will harm an unborn baby.”

How have these vaccine recommendations worked out for pregnant women and their babies? Published reports point to an increased risk of miscarriages and elevated risks of birth defects and autism in the offspring of mothers who received influenza vaccines during pregnancy—described by World Mercury Project on multiple occasions. Although evidence about Tdap is still emerging, the global VigiBase database (launched in 1978 to collect reports of vaccine-related adverse events from heterogeneous systems in 110 countries) indicates that three-fifths (58%) of all the Tdap-related adverse events reported to VigiBase have occurred since 2010, half (49%) have been in females and 7% have been in the 18-44-year age group. Admittedly, the non-systematic nature of the VigiBase data makes it difficult to interpret these trends, but it still seems surprising that the default official position shared by academics and regulators is that “there is no documented causal evidence of developmental or reproductive toxic effects in humans following the use of [any] approved vaccine.”

Looking back

Prevailing notions of what is “ethically permissible or necessary” with regard to the medical protection of pregnant women appear to be somewhat malleable. There was, in fact, a time when regulators did not display the same levels of insouciance about vaccine and drug administration during pregnancy. Formerly, federal policy (at least on paper) deemed it prudent to exclude women of childbearing age and pregnant women from taking part in clinical trials to test new drugs. This precautionary stance—grounded in established toxicological principles—aimed to forestall developmental toxicity disasters such as the one that occurred with thalidomide. In 1993, however, mounting pressure from various sectors persuaded the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to abolish the perceived “medical research gender gap.” The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) reversed course and began encouraging routine inclusion of reproductive-age women in clinical trials—but it continued to note the special circumstances of pregnant women (and is just now getting around to formalizing scientific and ethical guidance pertaining to pregnant women’s participation in drug trials).

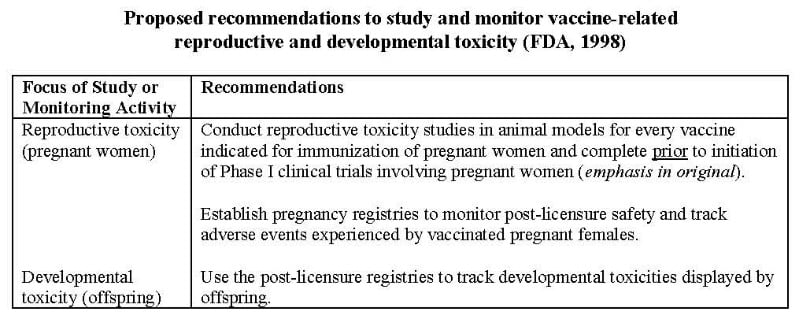

Over at the FDA’s sister office CBER (Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research), which oversees vaccines and other “biologics,” officials initially seemed to share CDER’s apparent restraint concerning pregnant women. In 1996, CBER’s Office of Vaccines Research and Review (OVRR) wrote up a detailed two-page memorandum on reproductive toxicity and vaccines. It then invited the public to submit written comments(in 2000) and eventually published “Guidance for Industry: Considerations for Developmental Toxicity Studies for Preventive and Therapeutic Vaccines for Infectious Disease Indications” (in 2006).

The memo and subsequent guidance spelled out the critical need to conduct preclinical studies in animal models to assess reproductive and developmental toxicity “prior to licensure of vaccines intended for maternal immunization and/or women of childbearing age” (see table below). However, the documents admitted that “lack of adverse effects on embryo/fetal development in an animal study does not necessarily imply absence of risk for humans.” Moreover, given the FDA’s emphasis (in a header on every page) that all of the recommendations included in its guidance are non-binding, the extent to which vaccine manufacturers choose to abide by them is largely unknown.

…neither the FDA nor the WHO commented on the possible conflicts-of-interest inherent in having vaccine manufacturers conduct their own pharmacovigilance.

In 2013, when the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety reviewed the safety of the growing number of vaccines intended for pregnant women, it noted “the limited amount of clinical trial data on pregnant women” and, like the FDA, emphasized the importance of “enhanced pharmacovigilance in the post-licensure phase.” However, neither the FDA nor the WHO commented on the possible conflicts-of-interest inherent in having vaccine manufacturers conduct their own pharmacovigilance.

Numerous challenges

Even under the best of circumstances, vaccine development for pregnant women poses special challenges. As one researcher recently stated:

“Not only do vaccines for pregnant women require evidence of immunogenicity, potency, stability, and limited reactogenicity, they must also provide efficacy in decreasing morbidity for the pregnant woman, her fetus, and the neonate, demonstrate safety or lack of evidence of harm, and offer benefit or potential benefit of vaccination during pregnancy.”

Conducting the types of preclinical developmental toxicity studies and after-the-fact monitoring activities described in the FDA documents comes with its own set of challenges. These include:

- Identifying suitable animal models for preclinical studies, particularly because not all species (e.g., primates, rodents or rabbits) are appropriate for all research questions.

- Assessing whether adverse effects on the developing embryo or fetus were caused by the vaccine antigen or by other vaccine constituents (such as adjuvants, preservatives and stabilizers).

- Evaluating adverse influences of vaccine-induced antibodies on both fetal and postnatal

- Determining whether maternal vaccination affects immune development in the offspring.

Toxicologists also continually call attention to the fact that even very small doses of substances such as mercury “may cause extensive adverse effects later in life.” These experts emphasize that toxicity is both dose and time-dependent, and that toxicity testing must investigate time-dependent effects. The vaccines destined for pregnant women have not been subjected to this type of nuanced scrutiny.

Where are the warnings?

A recent assessment of titanium dioxide nanoparticles—a modern product included in many cosmetics and drugs—warned of significant and potentially devastating effects on “millions of pregnant mothers and their offspring.” Vaccines contain an array of nanoparticulate ingredients (some intended and some not), but no comparable studies have emerged nor have warnings been issued. In general, published discussions of vaccine safety during pregnancy exhibit a linguistic slant toward describing risks to the fetus as “perceived” and “potential” rather than actual. Whether regulatory agencies’ former professed interest in protecting pregnant women from exposure to potential toxins was ever sincere or not, by and large, it appears to have become a historical footnote.

Read more at: WorldMercuryProject.org and see Vaccines.news for daily coverage on vaccine science.

Tagged Under: Big Pharma, Birth defects, medical malpractice, motherhood, open season, pregnancy, pregnant women, toxins, vaccination, vaccines